This puzzle is a PowerPoint presentation. After clicking the start button, there are five possible buttons to press on each slide: the four arrows as well as the center circle. Pressing the arrow rotates or pans the view in the corresponding direction, and pressing the center circle either moves the view forwards through the slide or flips the view to the opposite side. Moreover, most slides have gray lines on some of the edges. Assuming that the slide transitions are geometrically accurate, we can determine that the slides represent all the faces of a 2 by 2 by 2 cube, including the dividers that separate the interior into eight 1 by 1 by 1 cubes.

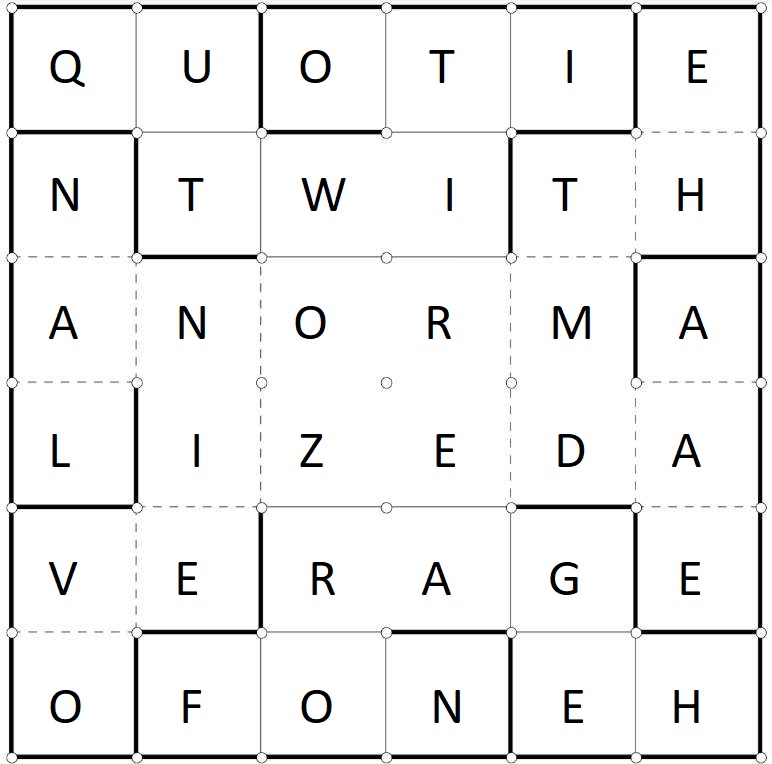

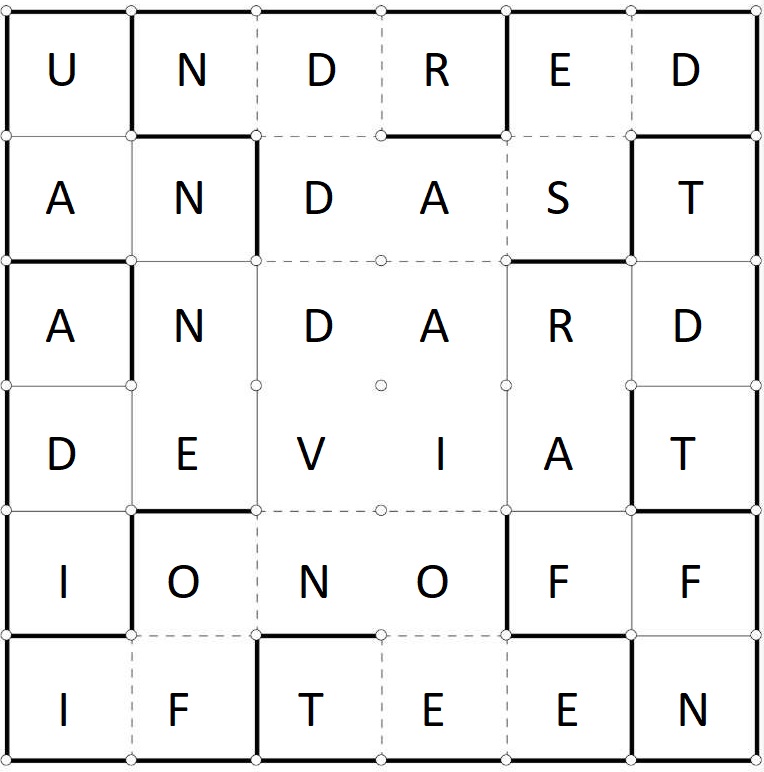

As clued by the flavortext, the next step is to unfold the cube. To do so, we can construct the cube from paper, and then cut along the gray lines on some of the faces (this disconnects each face from its neighbors along the gray lines). After cutting, we can then unfold the cube into a flat 6 by 6 square, with letters in a uniform direction on each side:

The thick lines are where the paper is cut, the thin solid lines are mountain folds, and the thin dashed lines are valley folds. All folds are exactly 90 degrees.

QUOTIENT WITH A NORMALIZED AVERAGE OF ONE HUNDRED AND A STANDARD DEVIATION OF FIFTEEN refers to the intelligence quotient (IQ), and hence the answer is INTELLIGENCE.

Here are some animations showing the folding and unfolding of this cube (made using Origami Simulator):

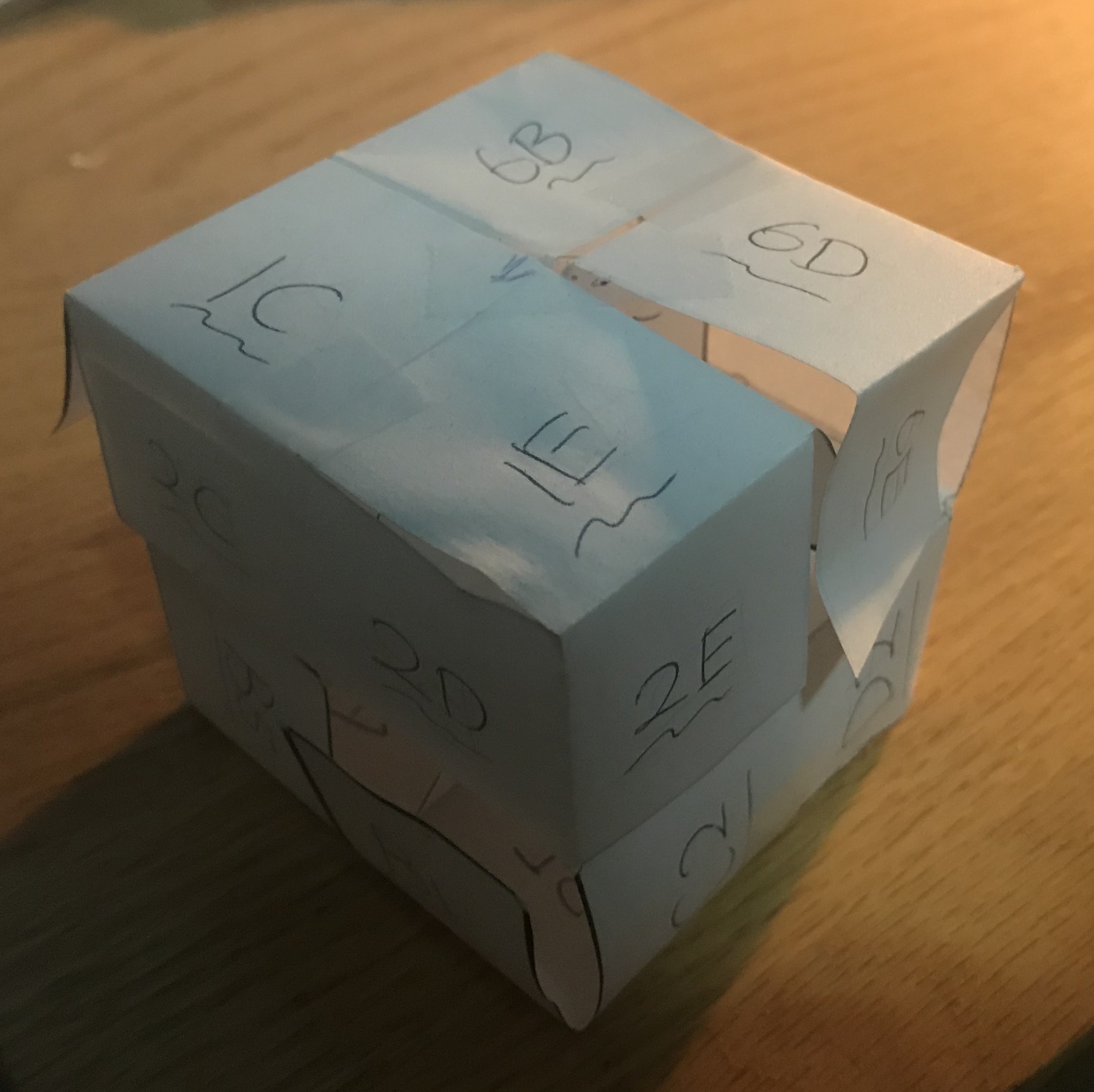

Here is a folded version of the cube in real life (with generic labels on each face) that was used to aid in the construction of this puzzle:

Author’s Notes

When I was young, there were not many software applications on our family computer, although it did have Microsoft Office (2003?) installed. As I didn't quite know how to browse the internet or play video games at that age, a large fraction of my computer screen time was spent playing around on PowerPoint, without even knowing what a "presentation" or a "slideshow" was. PowerPoint had a lot of features that resemble both a professional drawing application and a game engine (with all the fancy animations and transitions), which allowed me to have fun just trying random things without anything specific in mind. At that time, people also frequently shared interactive PowerPoint files (like short animations, quizzes, and even mazes) via email, and my parents would sometimes let me play with ones they received from their colleagues as well. While I never understood how those files were made, they definitely were some fond memories from my childhood.

After watching Tom Wildenhain's legendary video on the Turing completeness of PowerPoint more recently, I was inspired to make a fully interactive puzzle using PowerPoint. As opposed to the various animations that allowed for Turing completeness, I was more interested in the different slide transitions that looked like traveling in physical space. This lends itself well to a (text-)adventure-esque puzzle, although I didn't have a good idea for how to turn an adventure into a puzzle.

Later, when working as a teaching assistant in a math summer camp, Sasha Rudenko (former deputy leader of the USA IMO team) told me a math problem from a Russian math Olympiad, which asked whether one can cut and fold a 6 by 6 square into a 2 by 2 by 2 cube, i.e. the reverse process of this puzzle. (I could not find the precise source, so let me know if you have it!) As my intuition was leaning towards the negative, I was shocked to learn that this was not only possible, but also with a rather symmetric construction (see above). This fact was so beautiful that I had to somehow make it more widely known.

These two concepts naturally came together for this puzzle, although it was not until 2019 that I first proposed this idea for GPH 2020. When we won the Mystery Hunt last year, this naturally ended up in a proposal for MITMH 2021.

The construction of this puzzle was surprisingly difficult and time-consuming. Besides having to make a slide for every position and orientation, a major obstacle was that one can only add slide transitions between adjacent slides (more precisely, the transition is associated with the target slide, so when one clicks a hyperlink between slides, the transition only depends on where the hyperlink goes to). This means that I in fact had to make each transition separately. This results in 72 (faces) x 4 (orientations) x 5 (transitions) = 1440 slides in total!

There were many attempts at reducing the workload using symmetry: the transitions of one interior cube were built first, then copied 7 times and connected to each other. One half of the exterior was then built and then copied to the other half. The gray lines were added individually, although with some attempt at a systematic process to maximize copy-pasting and minimize errors. I also built a real-life paper cube (see image above) to keep track of the orientations of labels. Generic labels (e.g. A1, F4) were used in the prototype to allow for easy substitution of cluephrase (via search-and-replace). All in all, this puzzle took roughly one month to construct.

Being one of the less programming-adept members of the team, I used no programming during the construction, except for a very simple VBA script to underline all the letters to disambiguate orientation and change line thickness/color to make the gray lines more visible after some testsolver feedback. In retrospect, maybe I should have written a program to construct the slideshow, but it is not clear whether the complexity of this puzzle would make my life much easier. Also, who wants to learn Visual Basic anyways?

It is unfortunate that other slideshow applications do not handle the transitions the same way that PowerPoint does, which made this puzzle less accessible than I had originally hoped. (Earlier versions of PowerPoint also had vertical flips instead of horizontal flips, which confused some of our testsolvers.) Nevertheless, I hope that you enjoyed exploring this puzzle in such an unusual medium, and experiencing the power of slideshows the same way I did in my childhood.